How did I get here? Well, there are many stories that brought me to after BREAST CANCER, stories about my treatments, my surgeries, my recovery, about my family and friends. But what delivered me to the doors of after BREAST CANCER merits its own telling as it an undeniably memorable and, in some ways, necessary as that very day changed my altered bodily image for the better.

Every woman knows that before and, especially after a mastectomy, half this experience is emotional and psychological. Hell, the half the cancer battle is mental, the other half physical regardless if the person does not want nor know how to acknowledge this very real fact.

I was ready for my mastectomy—as much as anyone can be ready for a part of their body to be lopped off. I thought about surgery for almost 8 very long months. If you ask me (and you did not but I am going to tell you anyway since you are here), too long, too much time to think or overthink. As my pragmatist and dedicated surgeon reminded me in the weeks before my mastectomy, 8 months after diagnosis allows to much mental time. I waited a lot longer than most women for surgery and that can cause very dangerous mental gymnastics. And, at times, it was. I was more scared of the surgery than what I would look like after losing my breast as I had come to terms with that (if that is possible).

But, I was calmly okay when I first looked at my “new” (remember, I did not say deformed as it is not deformed—it is healed of cancer) body. The day my nurse removed the last of my Steri-strips (kudos to the dynamo named Lolita who made sure I healed with wit and professionalism), I did not look. I needed a day. It is in this time I raged against the proverbial machine, a time when I determined what I needed or just absorbed what is/was happening. Throughout my entire experience, I always needed and still need a day to process what I hear, what is happening. This day was no different. The mental game.

My mother said that I would look at my newly re-scripted, re-defined chest when I was ready. She, ever able to read me and a situation, was correct. Yet, I knew waiting too long was not healthy. It is a

form of denial: it happened, it is done, it is what it is as they say. The next day, after I stepped out of the longest and most glorious shower of my life (13 days is a long time to sponge bathe and this shower was unquestionably more luxurious and needed than the shower I after delivering my child), I looked. For about 90 seconds. I did not dwell; I did not cry. I just looked and absorbed the image of the new me. I might have just shrugged. I had placed a wash cloth over my right breast when first diagnosed trying to envision what it would look like. This looked better than that.

It was okay. It really was and I was fine, mentally and emotionally good. I knew from the bandage what flat looked like. The bare, scarred skin showed me how truly different I was but, I was impressed at what an amazing job my surgeon did. I was okay with having one breast. It was odd, it was eerie in many ways—please do not get me wrong—but I had perceived in moments of raw emotion much, much worse. You might

know what I mean. Those dark moments, usually in the dark or in the wee morning hours while the world sleeps, your mind perceives things so much worse, so much more horrible and deformed. Perhaps, I believed I would be no longer a “whole” women. But I was okay, and was whole woman in almost all ways. I was still me, living and vocal and determined.

And then, all that known and accepted, I was not ready for what would happen next…

When I went for my surgical post-op exam, my surgeon recommended that I return to surgery to excise more nodes. 3 or the 4 of the those removed were cancerous. He seemed shocked—perhaps not as shocked as I perceived, perhaps a bit surprised—as I had undergone chemo and radiation prior to surgery. As I tried to process another surgery that was not rebuild—I could not rebuild because of radiation before surgery—the nurse navigator was yammering on about prostheses. I just blinked at her. Indeed, I did not hear a damn thing. This woman was the adult voice in in a Peanuts cartoon: wawa, wawawa.

Three days later, I landed flat on my chest as a bus stopped (too?) fast. Wow that hurt, like really really-screaming in my head, swearing worthy hurt—but I did not scream aloud as my 11 year old was scared by the look on my face. And it hit me, like the bus floor which was dirty and a cold slap as it were, that I needed a fucking prosthesis and fast. This thought continued to nag me as I held an ice pack to my chest hoping that I had not broken the chest bone or reopened the wound site. But nothing is simple. There were still several caveats or glitches to come.

I opted to go back to surgery and that meant another 6 weeks post-op before I could even consider getting a prosthesis. In that time, and the time that followed until I got my prosthesis, I was comfortable with my body (although seeing staples the second time around was a bit jarring) but not in my clothing. Clothing is part of our identity—of how we present ourselves to the world and how we present ourselves to our very selves—and if you cannot wear what you own, you do not feel like you entirely. Or, at least, that is how I felt. If I feel bad, I look good. That has been my motto for years and it is still applicable. Quasi-psychology perhaps but I was my mantra.

Wearing loose clothing was acceptable when it was hot and summery but as the season changed, my attitude changed with it. I started feeling out of sort, perhaps depressed, perhaps the thought that this trip from hell was still not over (and it wasn’t, I still needed rebuilt but that was a long-term vision not a prescient one).

I explain this how I felt rather simply: while in chemo, I had no hair but, I could wear my clothing, even with a Pic line). I rocked a scarf and was a nice touch to my dresses. I saw it as an accessory at times. After my surgery, my I had hair (very short and then very curly which was new to my life and made me self-conscious as I have always been very adamant about perfect hair, but I had hair) but I could not wear my clothing. One without the other was fine. Hair was easy for me to lose as then the perfect coif was not possible (that will be another writing adventure). Living unable to wear my fall/winter clothes, which is almost fitted dresses or shirts bothered the living $%#^ out of me.

I confess, I did not have large décolletage to begin with but still….really? And I did not have the money buy another entire wardrobe. Then it really hit me.To add insult to injury—figuratively and literally—I lacked the funds to buy mastectomy bras and a prosthesis. Now what? What next will happen in this jarring experience? Go without the needed chest protection and not be able to wear my clothes while feeling horrible which depressed me and then add in the very real fact that I could not afford what I needed so desperately for my mindset and my potential physical well-being. I repeat myself a lot and I will once again, 50% of this experience is mental. The after effects and the needs after treatment and surgery do not change that. There is the residual emotion and new emotions that emerge that you did not even think about or care to think about until necessary.

It is very simple—this is a process that changes the rules every so often that a person has to re-think and re-clarify emotions and learn to feel and process new ones.

So, I grabbed the papers I was given the dastardly day with the nurse navigator and started calling around to find out the cost of a “falsie” as my grandmother would have said and the bras that are made for them. I felt defeated almost instantly. It is insulting to me that after a woman goes through all these physical and mental hurdles that the costs associated with feeling “normal” again is so outrageous. Confidence is something women who have undergone mastectomies need a bit of help rebuilding (or at least me) and it is prohibitively expensive for a lot of us. To re-start life, to return to work, to be comfortable socially and professionally, to be at ease with our altered bodies should not cost this much money.

And, here in Ontario, the government only gives you less than half the cost and only after you buy the prosthesis. Bras, well, it seems they are not needed and, hence, no help. Pay first, get back—60 to 90 days later an amount that does not get you more than one bra (and if you have one breast, it needs some support) and less than 50% of the cost of a long-lasting and well-made prosthesis. Cancer took my hair, my eyelashes, my eyebrows, my breast, my ability to heal quickly and then takes my ability to wear my clothes and feel like myself with an eye to moving forward.

Now, I am not unique; I am not the only woman who cannot afford these “things.” I remember, sitting on the floor of my kitchen, blaring music in the dark, crying and shredding the papers with the phone numbers of places to get the requisite accouterments. Luckily, I did not finely rip those pages to shreds. Enter after BREAST CANCER, Alicia, Natasha and the amazing supporters and volunteers who help and change the lives of women like me. The next day I called after BREAST CANCER and found that I could get help. I was giddy, stupidly giddy. A new fake boobie? For me? Finally? I decided that I would live large and buy myself a dress that was very me, very long and very contoured. And I daringly wore it to my fitting in hope of seeing myself as a woman not a cancer patient. I sat with Alicia for an hour; telling her my story, telling her my emotions about this whole process and said, “I am done crying about this.” I did not cry often through this entire process—I cried but not constantly. I was fitted with a temporary prosthesis and given a bra to put it in. I put my dress back on. I stood tall and straight and….

Then I cried and I cried, oh, just in case, you don’t understand, I cried some more.

I will say that only two times in this battle have I cried tears of joy. The first was when I found out prior to my surgery that I did not carry the gene for breast cancer—and as an Ashkenazi Jew the risk was high—and that my daughter, my niece and my nephew would not have to be monitored throughout their lifetime for breast cancer. It meant my brother was not at a higher risk for prostate cancer. It meant I did not have to tell my daughter when she was in her mid-teens that she would begin screening at 18. And now, I cried again.

I walked out and looked Alicia in her caring eyes and told her: “I lied, I am going to cry.” And boy did I—I think her shirt needed to be wringed out after I picked my head off her shoulder. I felt like me. I looked like me. Although the hair was different as can be, I saw myself as whole.

And for the first time in months, as I walked out of after BREAST CANCER, I walked completely erect (no more slouching) and stood tall. That experience, in and of itself, changed me in ways I still cannot explain but I hope this does it some justice. after BREAST CANCER helped me almost completely close a circle that had begun 23 months before.

And gratitude is not a strong enough word. Gratitude might be one of the most important emotions any person can have. So, thank you after BREAST CANCER and its supporters. Thank you Alicia and Natasha for being so helping me start the next part of this “journey.” For being so helpful and so generous with your support, help and conviction to helping all woman move beyond breast cancer.

I was going to write a lighter, funnier post following my last one. But for some reason—writer’s block, lack of humor these days, perhaps—I just could not come up with a funny post. Humor is so important when facing treatments and surgery but sometimes, but humor can take too much energy.

So, instead, I will write about telling my daughter I had cancer. She was 10 at the time. Her father already was aware of my diagnosis of stage three lobular breast cancer but, I decided not to tell her until I had her with me for the weekend. Two days—two days from diagnosis, two days to begin processing the news before telling her; two days to have one night of crying and trying to get a grip on this monster. The day I was diagnosed I attended a performance by my daughter and I can honest write that I do not have any recollection of that night. I have been told she was outstanding that night. But, I was reeling. And I was still reeling when I told her yet, I needed to speak my truth. Many people questioned the speed with which I chose to tell her. At that time, I did not know the course of my treatments and surgery. I already knew that surgery and chemo were on the table and that I would lose my hair. Beyond that, how long of chemo, what kind of surgery? I knew nothing.

My daughter, the child I felt kick, I felt on my breast, the child who maddened me and made me laugh. She was, as I call her, an octopus. She latched on and even if I did not have that instant “yes, I am mommy” moment, she was attached as was I. I had to tell her because it was written all over my face. Even a 10 year old would know that something was not right, that something was wrong, very, very wrong.

Jr (as I call my daughter) and I were sitting in the den watching TV. I told her I needed to have a serious conversation with her. She rolled her eyes as 10 years old kids are wont to do. I think she thought the topic would be sex or something of that ilk but that conversation had already occurred and there was no “new” information to tell her as it were. Sadly—or perhaps for the best—I just blurted it out: “I have breast cancer.” Her reaction was what one would expect from a child not old enough to process this news easily (hell, I was still processing) but old enough to know what cancer means and what it could really mean.

She started crying and hid under a blanket for 10 minutes. I just sat there, letting her cry and feel her emotions. Then, figuring that was enough time, I pulled the blanket off her and restarted the conversation.

I reminded her of two very dear people who are close to her—one male and one female—had gone through breast cancer and survived. I reminded her that both people were healthy again and cancer-free. But, they are not mommy. They are not the person who is supposed to bring her to adulthood and guide her even if she kicked and screamed all through her teenage years. She saw mortality—mine—for probably for the first time.

I then put it to her as bluntly as possible: “I will be taken out by a TTC streetcar before this kills me.” That become my mantra with her through this long process.

I wanted her to come with me to get my hair buzzed off before I lost it to chemo but she would not. I think, in hindsight, just the same as I did then, she could not. I was hoping to make her laugh yet she did not find any humour in this. I did but that is another story (a story of clippers, a flagon of beer and a barber who made that experience the best possible and it was a very funny and fun experience that allowed me to have control over losing my hair). Anyway, back to Jr. She was with me the night after my first chemo and I had no idea how it would hit me. It was New Year’s Eve (15 days after diagnosis) and I could not stay awake. I think it really sunk in for her that night.

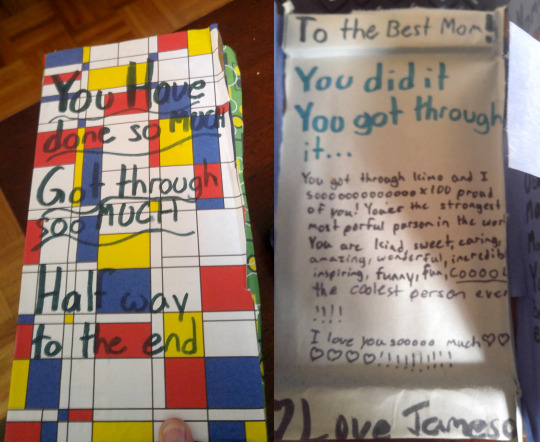

As I went through chemo, my goal was to show her perseverance. Even if I was tired and my legs ached from the combination of chemo and Neuprogen, I made sure we did something, that we went out even if only for an hour or two. I wanted her to see that carrying on as normally as possible was not only a strategy for life in horrible circumstances but almost an act of defiance. Having written that, if I could have taught her anything in those months and the months of radiation and then two surgeries, it was strength is within and you can crumple or you can just keep going. After the last chemo treatment, she gave me this. And I am proud of her and her ability to make this card. And I am proud of her now, 2 years later, as she makes jokes about when I had no hair, about my “ta” as “you don’t have ta-tas.” I see resilience.

Let’s talk about hair. All hair, hair on the head, hair on the legs and arms, hair under said arms, hair in the nether-regions, eyebrows and eyelashes. Hair is one (of many) defining features of someone. Think about it—you describe a person as having short hair, bald, long hair, unshaven, shaven, what color hair, etc. You wear a haircut that suits your face, your style, your personality. Your wear your hair. And on bad days (and good), it wears you.

Now, when you are told you will lose your hair because of chemo drugs and, do not kid yourself, all breast cancer chemo does cause hair loss, it is disconcerting and as if a part of your identity will be altered in ways you cannot imagine. It is a tell-tale sign that you are sick and under treatment; it will possibly change how you how see yourself and how other people see you, even those close(st) to you. Yet, despite the requisite “balding”, there is another side, a potentially positive side: the merits of not having to shave, wax and such if that is your thing.

Losing your hair might be something that you can control to a point, something you can make your own. Yet this depends on mindset and comfort. When I was diagnosed, the person with me looked at my oncologist and said: “I have to ask the elephant in the room.” Without missing a beat, my doctor said “100% within 3 weeks.” Ouch. Okay, so now what? I always had a bob. It was me. It defined me—a perfect bob off and on for 22 years and mostly on. I immediately knew what I had to do. I emailed my hair stylist and she sent me a picture of a pixie cut. I wanted to immediately cut my hair. Maybe cutting it off so quickly after diagnosis was a way for me to accept what was about to happen. My daughter, however, was freaked out by the idea of this decision since she could not even process my diagnosis. I, however, thought: why spend that much money for a few weeks? Then, a friend who had gone been through this dastardly process said two words. Very simple word: buzz cut.

I was not averse to the idea in the least but, her explanation was/is rational and needs to be told to people about to go through this. Cutting your hair, at least for her and myself, is an act of control and one of mitigating the emotional effect of this craziness. Your hair is coming out—you have no choice about it—and it will come out all over the place and mostly in the shower. So, if your hair is still long(ish), it will clog the drain.